-

About

-

Academics

- Physician Assistant

- Special Master’s (MBS)

-

Admissions & Financial Aid

- Tuition & Fees

-

Student Life

-

Research

- Research Labs & Centers

-

Local & Global Engagement

- Global Health Program

Finding a Gene That Regulates Sleep

Tufts researchers discover a gene necessary for maintenance of healthy sleep in fruit flies, which might help understand human sleep

What keeps us awake—and helps us fall asleep? The answer is complex, but involves what are called circadian rhythms, which are found in all species with sleep-wake cycles—physical, mental, and behavioral changes that follow a regular schedule.

In most animals, that cycle is twenty-four hours, and is dependent on environmental signals like light. It is regulated by a “master clock” in animals brains, comprised of a group of neurons regulating sleep and other circadian processes. Sleep is also, of course, regulated by so-called “sleep pressure,” which comes into play when humans or other animals are deprived of sleep.

Rob Jackson, a professor of neuroscience at the School of Medicine, leads a lab that has been studying circadian rhythms and their genetic basis for more than thirty years. He uses fruit flies—Drosophila melanogaster is the scientific name—to study the phenomenon, since they have twenty-four-hour circadian clocks and sleep cycles similar to those of humans. “Remarkably, many of the genes underlying their rhythmic behaviors have human counterparts,” he said.

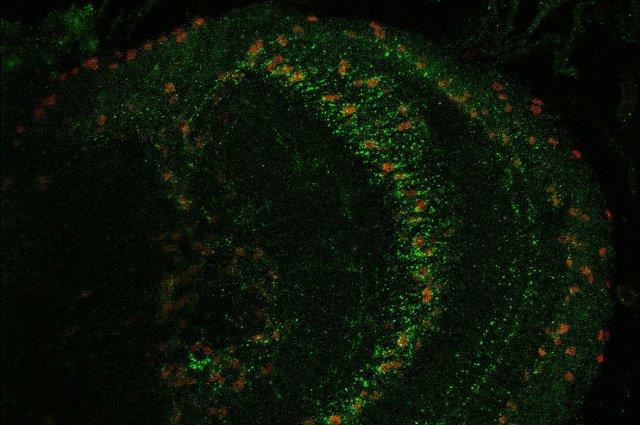

Jackson’s lab was the first to identify a critical role of astrocytes as important regulators of circadian rhythms. Astrocytes are glial cells of the brain that had long been thought of as support cells—brain glue, hence the name glia—but are now known to play much more important roles. Jackson and his colleagues also discovered that fly astrocytes secrete signaling factors to communicate with neurons, regulating sleep behavior.

Today the researchers report in a study published in Current Biology that a gene they named Noktochor (NKT) is expressed at high levels in fly astrocytes and is required for normal sleep patterns. Noktochor, which means “nocturnal” in Bengali, is not required during fly development, but is necessary in the adult brain for maintenance of healthy sleep, “suggesting a physiological function in adult flies,” said Jackson.

Fruit flies that lack NKT gene expression have decreased night sleep, while their sleep during the day is normal—and yes, flies take afternoon naps. The NKT gene is expressed at high levels in fly astrocytes and at low levels in their neurons, and is required in both cell types for normal night sleep.

In addition to Jackson, the research team included Sukanya Sengupta, Lauren B. Crowe, Samantha You, and Mary A. Roberts from Tufts University School of Medicine.

Tufts Now spoke recently to Jackson about the findings, and what they might mean for people suffering from sleep issues.

Department:

Neuroscience