-

About

- Departments & Offices

-

Academics

- Public Health

- Biomedical Sciences

- Physician Assistant

- Special Master’s (MBS)

-

Admissions & Financial Aid

- Tuition & Fees

-

Student Experience

-

- Student Resources by Program

- Academic & Student Support

- Wellness & Wellbeing

- Student Life

- Events & Traditions

-

-

Research

- Research Labs & Centers

- Tufts University-Tufts Medicine Research Enterprise

-

Local & Global Engagement

- Pathway & Enrichment Programs

- Global Health Programs

- Community Engagement

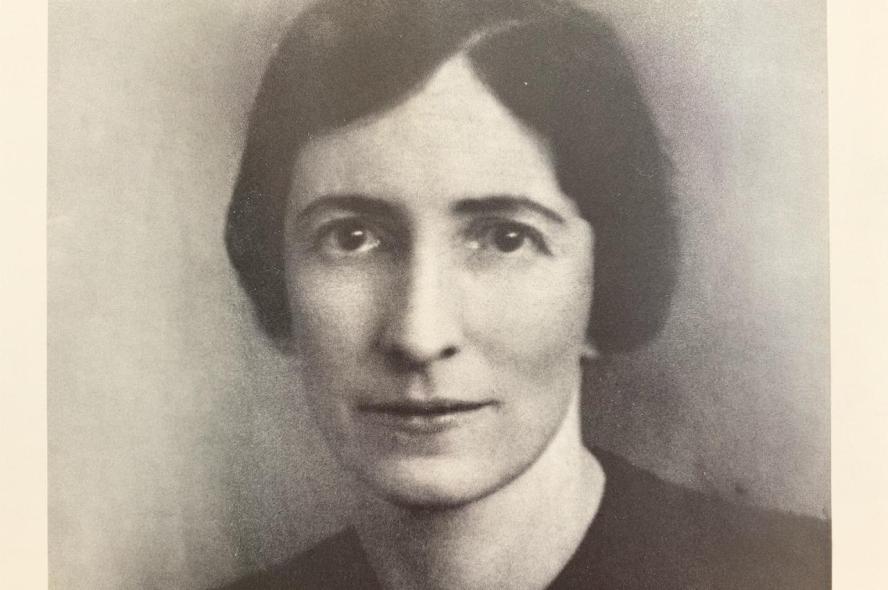

The Analyst Who Taught Freud a Thing or Two About Women

With her M.D. from Tufts, Ruth Mack Brunswick made a name for herself in Vienna and the new field of psychoanalysis.

One of Sigmund’s Freud’s most well-known cases was that of Sergeï Pankejeff, a Russian aristocrat who suffered from anxiety and severe depression. Freud wrote extensively about the childhood traumas he saw as the root of Pankejeff’s problems, with detailed analysis of the man’s boyhood dream of being terrorized by white wolves sitting in a tree outside his bedroom. The case was known as the “The Wolf Man.”

When the Wolf Man sought further treatment years later, Freud handed the care of his famous patient to his trusted protégé Ruth Mack Brunswick. Her paper about Pankejeff, according to the book Freud’s Women, “gives evidence of the terse brilliance with which Ruth handled clinical concepts and the incisive acuity she brought to summarizing the progress of a case.”

Brunswick, a 1922 graduate of Tufts University School of Medicine, was a member of Freud’s inner circle, a close friend as well as a respected clinical talent to whom he referred many patients. While she wrote few professional papers, those she did are considered significant in extending Freud’s theories.

Born in Chicago in 1897 to jurist and philanthropist Julian Mack and his wife, Jessie, Brunswick graduated from Radcliffe in 1918 with an interest in psychology. Denied entrance to Harvard Medical School because she was a woman, she enrolled at Tufts’ medical school, which had been coed since its founding in 1893. Degree in hand, the 25-year-old traveled to Vienna to train with Freud, the father of psychoanalysis. There she became one of several analysts Freud mentored, a surprising number of them female.

“Freud may not have been a feminist, but he had called his first women patients ‘his teachers’ and from very early on in the life of psychoanalysis, he was open to women becoming practitioners,” explained Lisa Appignanesi, co-author of Freud’s Women. Psychoanalysis was a new profession at a time when the women’s rights movement was advancing women’s education and their role in society. “Then, too, the psychoanalytic interest in the intimate, in sexuality and love, in childhood and domestic life, made it a very suitable profession for women.”

Paul Roazen, a Freud biographer, described Brunswick as “demonstrative and explosive, outgoing, effusive and warm. She was also an elegant person with cultivated manners, as well as vivacious and possessed of a lively intellect. … She was literate and verbal, well read, and one of the few Americans not stigmatized as an American in Freud’s eyes."

Brunswick became a conduit for Freud’s American patients, whom she looked after when they were in Vienna, as well as an interpreter of Freud’s theories for the psychoanalyst community in New York.

Brunswick, like her friend and fellow analyst Marie Bonaparte, was not afraid to correct Freud. “Both women were very good at countering Freud’s ideas about the feminine: the girl’s development, relations to mother and father, and sexuality,” Appignanesi said. “Freud mentions Ruth twice in his 1931 paper on femininity, pointing out what he learned from her and other of the young women analysts.”

According to the book Freud and Women by Lucy Freeman and Herbert Strean, Brunswick was one of the few people to whom Freud gave a cherished gift: a copy of an antique ring with a Roman seal. It was a sign that they were “loyal adherents whom he felt would continue to bring psychoanalytic findings to the world.”

As war loomed in the late 1930s, Brunswick helped friends emigrate to the United States, returning there herself in 1938.

Like all of Freud’s trainees, Brunswick underwent analysis, a process that she repeated with her mentor throughout her time in Vienna. Whether as an analyst or a friend, Freud counseled her on her two marriages, one to a heart specialist and one to a composer, both of which ended in divorce. Her health began to deteriorate, and in treating her own emotional and physical ills, she grew addicted to opiates, which may have contributed to her early death in 1946 at the age of 48.

While Freud’s theories remain widely criticized, he is credited with the idea that talking about oneself and one’s problems can be therapeutic and the recognition that the unconscious mind can influence behavior. Brunswick, in fine-tuning his ideas and spreading them in the United States, may have helped lay the groundwork for the mental health therapies we have today.