-

About

- Departments & Offices

-

Academics

- Public Health

- Biomedical Sciences

- Physician Assistant

- Special Master’s (MBS)

-

Admissions & Financial Aid

- Tuition & Fees

-

Student Experience

-

- Student Resources by Program

- Academic & Student Support

- Wellness & Wellbeing

- Student Life

- Events & Traditions

-

-

Research

- Research Labs & Centers

- Tufts University-Tufts Medicine Research Enterprise

-

Local & Global Engagement

- Pathway & Enrichment Programs

- Global Health Programs

- Community Engagement

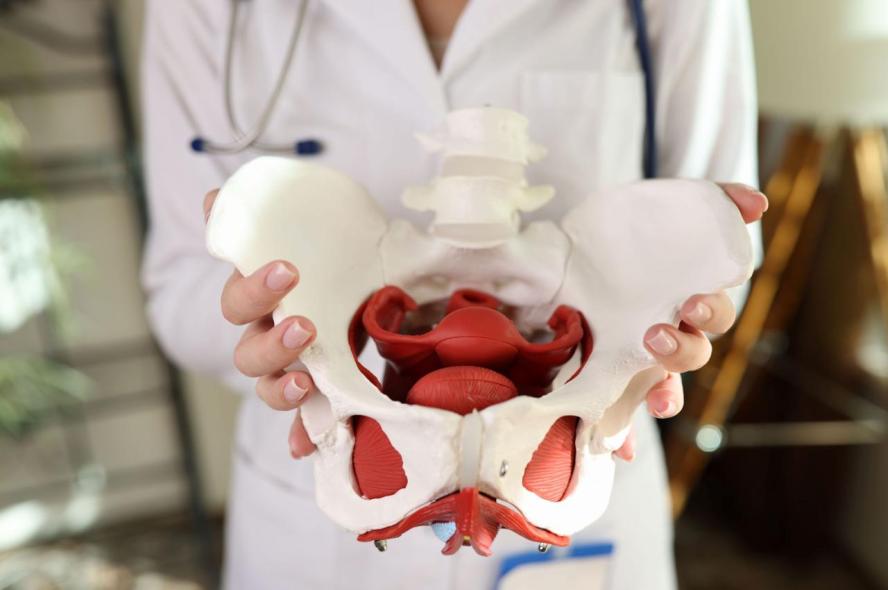

Let’s Talk About Women’s Pelvic Floor Health

A Tufts urogynecologist wants women to know there are treatment options available for pelvic floor dysfunction.

Bodies change as they age, especially after physically demanding experiences like pregnancy. Many of those changes don’t have to be permanent, including ones that can be the most uncomfortable to talk about.

One in four women over the age of 20 suffers from at least one pelvic floor disorder, which can include urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse, according to a 2008 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Evelyn Hall, a urogynecologist and clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Tufts University School of Medicine, said despite the prevalence of these disorders in women, most won’t seek treatment when they’re experiencing symptoms simply because they feel ashamed or are unaware that options are available.

“I see women in my clinic on a regular basis who have been suffering from pelvic floor dysfunction, like bladder leakage, for years,” Hall said. “We have research that shows people suffer for a median of seven years before they see a doctor. There is this feeling that these conditions are dirty or gross or problematic. People are nervous to talk about them.”

When working with patients in her clinic who may be evaluated for symptoms like a frequent urge to urinate, leaking urine, and a general feeling of heaviness in the vagina, Hall reminds women that the pelvis is an area of the body that is required to carry immense weight throughout a lifetime, regardless of pregnancy experience.

“People often are very embarrassed to talk to their family or to talk to their friends, but I encourage people to realize that this is something that we can help folks with, and these issues are very common.”

Evelyn Hall, urogynecologist and clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology

“Those muscles actually serve as integral support systems to those vital organs,” Hall said. “During pregnancy, especially with vaginal delivery, a massive amount of stretch and strain is put on those muscles, which can be torn. Women can also experience nerve damage in the pelvic region. All these injuries tend to weaken the muscles further over time.”

Hall wants women to know that although these may seem like unique cases that must be dealt with privately, the opposite is true, and that the stigma associated with them is changing.

“There's a lot of data that talks about social isolation because of pelvic floor dysfunction,” Hall said. “People often are very embarrassed to talk to their family or to talk to their friends, but I encourage people to realize that this is something that we can help folks with, and these issues are very common.”

Medical interventions available for anyone experiencing symptoms vary depending on the specific symptoms, Hall said. Initial treatment options include physical therapy which can strengthen or relax the muscles in the pelvic region and train the bladder to empty on a specific schedule. Other options for those suffering from bladder-related symptoms include cutting back on dietary bladder irritants like artificial sweeteners, caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine.

For more pronounced symptoms, providers may recommend interventions like a pessary, which is a small dish that is inserted in the vagina to help support the muscles and relieve a feeling of heaviness, or oral medications which can alleviate symptoms like an overactive bladder.

Before a treatment plan is developed, Hall works to make patients comfortable throughout the diagnosis process, which typically includes a comprehensive questionnaire, an ultrasound to examine the bladder, and a pelvic exam to physically evaluate the pelvic floor.

“I always tell patients that it’s their body and they can stop the exam at any time,” Hall said. “I utilize trauma-informed practices to make people feel safe and ensure they know they have control.”

Based on the findings, Hall will sit with the patient and have a conversation about what is going on in their body and what type of treatment options are available. “This is very much quality of life-focused,” Hall said. “It’s about a partnership.”

Hall shares each option and asks about the patients’ priorities and what treatments they’re most interested in trying. If they are a candidate for physical therapy, Hall will refer them to a practicing pelvic floor PT, which she notes can be weird, but can also be life changing if the patient gives it time and effort.

“As with any physical therapy, the most important thing is consistency,” Hall said. “For patients with urgency and frequency symptoms, physical therapists will work on strengthening the muscles and behavioral retraining exercises. For those with hypertonic pelvic floors, which causes a constricting of the muscles, they will work on stretching out the pelvic floor so that the pelvic length may be maintained, which should eliminate things like pain during intercourse and the feeling of urinary urgency.”

Physical therapy has a 50% to 60% improvement rate, Hall notes, and patients should begin to see positive change by the fourth session. And if symptoms aren’t changing for the better with physical therapy, it’s a good idea to get back in touch with a provider for a follow-up appointment.

Related Research at Tufts

Shefali Christopher, director of admissions for the Tufts School of Medicine’s Doctor of Physical Therapy program in Seattle and associate professor in the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, is an expert in pelvic floor dysfunction, specifically in athletes. She was inspired to pursue this research path after her own pregnancy and postpartum journeys left her with then-unanswered questions.

“I realized there was something missing because just like the women I was seeing in my clinic, as a new mom, I had questions about regular exercise and return to sport,” Christopher said. “Every woman who experiences pregnancy undergoes pelvic strain, but only a small population are seeking treatment in my clinic. So how do we, as providers, tailor our recommendations specifically to these patients?”

Now, more than a decade after her first child was born, Christopher champions taking an individualized approach to athletes’ postpartum physical therapy care, including pelvic floor support.

“By encouraging them to return to their pre-pregnancy routine, we are showing women in postpartum stages that they aren't made of glass,” Christopher shared. “It’s important for them to know they aren’t going to just crumble if they begin to exercise again.”

Research in the area of pelvic floor physical therapy is ongoing and is published in journals like the Journal of Women’s & Pelvic Health Physical Therapy (JWPHPT), where Christopher is an associate editor. She hopes that by sharing information about pelvic floor health with other physical therapists and with clinical providers, postpartum women can get answers and take control of their physical health.

Department:

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation