-

About

- Departments & Offices

-

Academics

- Public Health

- Biomedical Sciences

- Physician Assistant

- Special Master’s (MBS)

-

Admissions & Financial Aid

- Tuition & Fees

-

Student Experience

-

- Student Resources by Program

- Academic & Student Support

- Wellness & Wellbeing

- Student Life

- Events & Traditions

-

-

Research

- Research Labs & Centers

- Tufts University-Tufts Medicine Research Enterprise

-

Local & Global Engagement

- Pathway & Enrichment Programs

- Global Health Programs

- Community Engagement

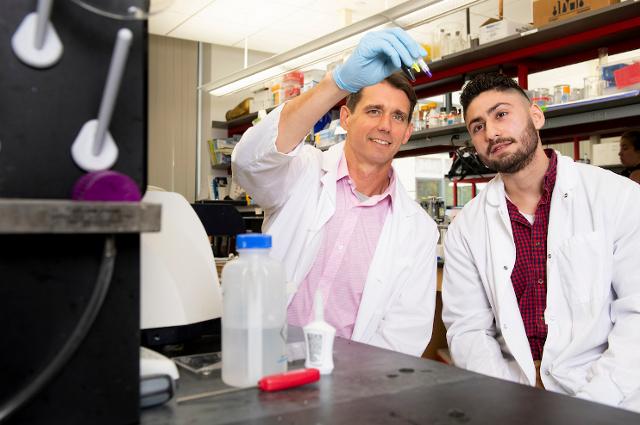

Science Is Hard—Here’s How Mentors Make It Easier

Recognized by the NIH for his mentoring skills, scientist Chris Dulla offers some advice for mentors and mentees

Part advisor, part guide, part therapist—a good mentor is someone who can make all the difference in a career, especially if that career starts in a laboratory. Studies have shown that good mentorship leads to more productive, successful scientists. Chris Dulla, an associate professor of neuroscience at the Tufts University School of Medicine, knows something about that.

In September, Dulla received a Landis Award for Outstanding Mentorship from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, part of the National Institutes of Health. He received $100,000 to help advance the careers of students and postdocs in his lab. The award noted that Dulla is known as “a person to call on when students have career challenges to overcome.”

In July, he and Ph.D. student Sadi Quiñones were awarded a Howard Hughes Medical Institute fellowship to improve mentoring skills, support scientific leaders, and foster diversity in science.

Dulla, who still consults with the mentors he had as a graduate student, postdoc, and new faculty member (“It’s good to have someone with experience to give you reality checks”), talked with Tufts Now about why he mentors and the advice most new scientists need to hear.

Tufts Now: Why is mentorship particularly important in the sciences?

Chris Dulla: In science, there are just so many career options—you could go into industry, or academia, or consulting, or journalism. When students come in, they may not even know what the options are. Many faculty members know what’s out there, what the student’s strengths and goals are, and what’s going to work for that student.

Another reason is that being a scientist is really hard. Most of the things you try are going to fail. And people who have been doing this a long time know that. So having someone there who supports you and has compassion and can say “If this was easy, everyone would do it” is important.

I’ve read that bench scientists can be particularly isolated and susceptible to burn out. How can mentors help prevent that?

I try to show students and postdocs that even though this career is challenging, it’s fun and exciting. It has a lot of rewards, both personal and professional. We are trying to help people by treating diseases, so I try to make that clear to them that their projects are meaningful, that when we have a new paper we will go to a conference to share our data and get new ideas from people around the world.

What is a lab director’s job, besides teaching lab skills?

It’s fostering all the skills that students need, whether that’s writing and communications, navigating politics, building professional networks, or resolving contentious situations with their colleagues. And it’s promoting students, just like Phil Haydon [Annetta and Gustav Grisard Professor of Neuroscience] promoted me when I was a new faculty member. It’s grabbing someone at a conference and saying, “Come look at my student’s poster, this is really exciting.” Because students are shy; they don’t want to put themselves out there. I definitely view it as my job to promote them in that very direct and personal way.

I can see why mentorship is good for the mentee. What does the mentor get out of it?

It’s not selfless, to be honest. One of the best parts of this job is that you’re always getting to work with the new young people. They have interesting ideas and they challenge your ideas. Sometimes I might take something for granted—“we already know that”—but then a student will come in and ask a really good question. I might not want to deal with it because it makes me rethink everything, but that’s how you advance things, that’s how you discover new things. I definitely get a lot out of it.

What’s one piece of advice you always give young researchers?

Most people who come into the lab are pretty driven and smart and ambitious. So sometimes I think the best advice is to relax a little bit. Don’t define yourself by your work. Things are going to go wrong, and just because your idea didn’t pan out, it doesn’t mean you are a bad scientist. Have fun. Enjoy the people you work with, your time in the lab, and the time you spend thinking about the work.

Department:

Neuroscience