-

About

- Departments & Offices

-

Academics

- Public Health

- Biomedical Sciences

- Physician Assistant

- Special Master’s (MBS)

-

Admissions & Financial Aid

- Tuition & Fees

-

Student Experience

-

- Student Resources by Program

- Academic & Student Support

- Wellness & Wellbeing

- Student Life

- Events & Traditions

-

-

Research

- Research Labs & Centers

- Tufts University-Tufts Medicine Research Enterprise

-

Local & Global Engagement

- Pathway & Enrichment Programs

- Global Health Programs

- Community Engagement

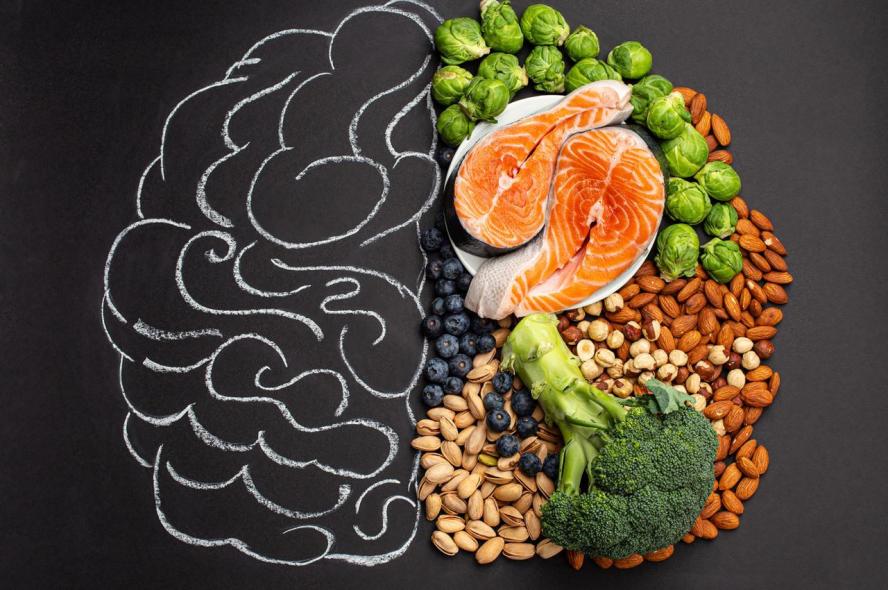

Tips to Protect Long-Term Brain Health

Emerging research is adding to our knowledge of how lifestyle choices can help prevent and slow the progression of cognitive decline as we age

This article originally appeared in the Tufts Health & Nutrition Letter, published each month by the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy. For more expert guidance on healthy cooking, eating, and living, subscribe here.

There is a growing understanding of the role lifestyle choices play in preventing and slowing the progression of cognitive decline. While we await new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease and other age-related dementias, emerging research can offer some advice for keeping our brains healthy and sharp.

1. Eat Minimally Processed Plants. “We know that a Mediterranean-style dietary pattern (which is high in minimally processed plant foods) may help delay age-associated cognitive dysfunction and probably prevent or delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease,” says Richard Dupee, A67, M71, chief of geriatrics service at Tufts Medical Center and clinical professor at Tufts University School of Medicine. Researchers are working on getting more detail on what roles different nutrients play in this relationship.

The new study: Researchers studied the association between dietary patterns rich in magnesium-containing foods and markers of brain health in just over 6,000 participants aged 40 to 73 years at baseline. On average, consuming more magnesium-rich foods was associated with larger brain volumes, especially in women.

What it means: While this study does not prove cause and effect, it suggests that increasing your intake of magnesium-rich foods may be good for brain health and, by extension, cognitive health. Magnesium-rich foods like leafy green vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, and whole grains are also packed with other beneficial nutrients. Whether it is the magnesium itself, or (more likely) a combination of factors, that is responsible for the observed association with brain health, choosing these foods in place of less healthy options is always a good idea.

What to do: Increase your intake of whole and minimally processed plant foods: Have a salad with leafy greens daily; choose whole grains and whole grain foods over refined; snack on a handful of nuts once a day, or sprinkle them on salads, whole grain low-sugar cereals, or grain dishes; and look for simple bean-based main courses or add beans to soups, stews, salads, and dips.

2. Avoid Ultra-Processed Foods. Ultra-processed foods generally bear little resemblance to whole foods, either in appearance or nutrient makeup. They are manufactured composites of extracted parts of foods, often mixed with artificial ingredients. More and more research is tying dietary intake high in ultra-processed foods to health problems.

The new study: Researchers looked at the dietary intake of over 10,700 individuals (average age, 51-and-a-half years) living in Brazil. Higher consumption of ultra-processed foods (including breads, crackers, cookies, candy, cereal bars, sodas, mayonnaise, sausages, ham, pizza, instant noodles and soups, deli meats, chips and other baked and fried snacks, and juices) was associated with a higher rate of cognitive decline in six to 10 years of follow-up.

What it means: Eating highly processed offerings may increase your risk for cognitive decline.

What to do: Focus on eating mostly whole and minimally processed foods. This means filling your plate with plenty of fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts/seeds, whole grains, seafood, lean meats, dairy, and healthy plant oils. Watch out, in particular, for foods with refined flour, added sugars, and lots of sodium. Foods loaded with processed protein isolates may also be problematic.

3. Listen Up. “As we get older, our hearing gets worse (more so for men than women, for whatever reason),” says Dupee. “There is no question poor hearing increases risk for loss of cognition.”

The new study: A study analyzed information from over 430,000 individuals aged 40 to 69 years. At baseline, participants were asked to report any hearing loss and use of hearing aids. Hospital records and death data were used to ascertain dementia diagnoses during the follow-up period. Compared to participants without hearing loss, hearing loss without use of hearing aids was associated with a higher risk of developing dementia. This association was not found in people with hearing loss who wore hearing aids.

What it means: Even if you have hearing loss, correcting the problem may help preserve brain function.

What to do: If you suspect you have any hearing loss or a family member or close friend mentions they have noticed a problem, it is important to be tested. If it is determined a hearing aid will help, get one. “There is significant resistance to getting hearing aids,” says Dupee, “perhaps because of appearance, or perhaps due to cost. If you can correct a hearing problem, do, not just for the sake of your hearing, but for your brain health as well.”

4. Get Moving. “Along with a healthy dietary pattern, regular physical activity is known to be important to preserving brain health,” says Dupee. “These are the same measures that protect cardiovascular health.” We know being active helps keep veins and arteries clear, which decreases risk for vascular dementia and strokes. Researchers are trying to understand other ways physical activity may help the brain.

The new study: It is suspected that physical activity causes long-term changes in the hippocampus, the part of the brain that controls the autonomic nervous system and is thought to be the center of emotion and memory. Working in a lab, researchers exposed hippocampal cells to chemicals released by contracting muscles. Neuronal activity increased and the number of cells increased rapidly.

What it means: In addition to aerobic activity (which increases heart rate and breathing), resistance training (which uses muscles against a force like a weight or band) may cause beneficial changes in the brain.

What to do: Get moving! Any kind of physical activity, in any amount, started at any age is beneficial to heart and brain health. “The current recommendation is to aim for 150 minutes a week of moderate activity, like gardening or brisk walking, or 75 minutes of more vigorous activity every week,” says Dupee. “Engaging in resistance training at least two days a week is also recommended.”

5. Tame Stress. “We do see that stress increases difficulty multitasking and adapting—especially in the aging brain,” says Dupee. “We also know that life stress, like the death of a spouse, is associated with higher risk for cognitive decline.”

The new study: A study assessed the level of perceived stress of nearly 25,000 participants aged 45 and older at baseline and at one follow-up visit. Cognitive function was assessed at the start of the study and annually throughout the study period. Higher levels of perceived stress were associated with about 40 percent higher risk of poor cognitive function.

What it means: If you feel you are under a lot of stress, you may be at higher risk for cognitive decline.

What to do: It may not always be easy, but stress can be managed. Think about what life changes (a new job, more vacation or personal time) you might be willing and able to make that could reduce the stress in your life. If you are a caregiver, look for resources that can give you some time off. Physical activity is a great way to relieve stress (and boost health!). Research also supports meditation as a way to relieve stress—even if it’s just setting aside a few minutes each day to close your eyes and breathe deeply. Laughter is another great choice, so find time to laugh with friends, go to a comedy show, or watch a funny movie. Get social, regular interaction with family and friends can help reduce stress.

Putting it All Together. These new studies reinforce our understanding of how lifestyle choices can help delay onset or slow progression of cognitive decline—even in people with a genetic predisposition to dementias. In addition to the behaviors discussed above, there are other things you can do that have been shown to help.

What’s good for the heart is good for the brain, so make sure you keep your blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol levels under control. If behavior change is not enough, medication may be necessary. Quality sleep is also essential. Work with a healthcare provider to address any issues interfering with your sleep. Research is clear that at least seven (but not more than nine) hours of sleep a night is ideal. Not smoking or vaping and being socially active are also important for cognitive health, as is learning new things. Doing the same types of puzzles you enjoy is not enough; make sure you are challenging your brain with new tasks to build new neural connections.

While there is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of age-related dementia, we are not powerless. Research is clear that healthy lifestyle choices and addressing health problems can help.