-

About

- Departments & Offices

-

Academics

- Public Health

- Biomedical Sciences

- Physician Assistant

- Special Master’s (MBS)

-

Admissions & Financial Aid

- Tuition & Fees

-

Student Experience

-

- Student Resources by Program

- Academic & Student Support

- Wellness & Wellbeing

- Student Life

- Events & Traditions

-

-

Research

- Research Labs & Centers

- Tufts University-Tufts Medicine Research Enterprise

-

Local & Global Engagement

- Global Health Programs

- Community Engagement

Staving Off Burnout

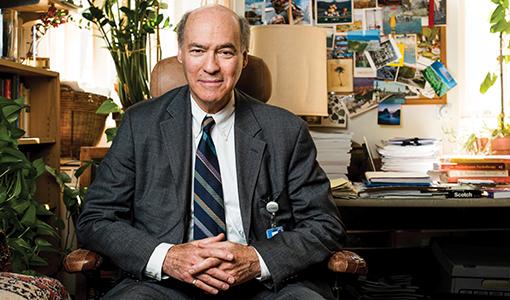

Jody Schindelheim, the director of medical student education in psychiatry and a clinical professor at the School of Medicine, helps budding physicians grapple with the emotional burdens of the profession.

Of the more than 14,000 U.S. physicians from 30-plus specialties polled for the 2017 Medscape Lifestyle Report, 51 percent reported feeling burned out—with emergency medicine, ob-gyn, and family medicine topping the list of the most stressed specialties. And compared to the general employed population, doctors worked more, displayed higher rates of emotional exhaustion, and reported lower satisfaction with work-life balance, according to a 2014 study by the American Medical Association and the Mayo Clinic.

“Medicine is a very intense field and a very intense life,” Jody Schindelheim said recently in his office. “I hope that for students, learning to put some of these experiences into words is an inoculation against depression, anxiety, and burnout.”

Since 1982, Schindelheim—the director of the adult psychiatry residency training program at Tufts Medical Center and the director of medical student education in psychiatry and a clinical professor at the School of Medicine—has been meeting with third-year medical students for an hour each week during their eight-week medicine clerkship. He books the room, convenes the meeting, and then mostly keeps quiet and stays out of the way as the eight to ten students compare notes and grapple with career decisions—required sessions that have affectionately come to be known as “Schindel-Time.”

“The clerkship is the first official time that students are being exposed to the medical system and its personalities at such close range as well as to some of the most emotionally laden moments in people’s lives,” said Schindelheim, who first came to Tufts in 1977 for his psychiatry residency. “They’re involved in very intimate working relationships and with patients from all walks of life who are in the throes of life-and-death situations.” While more experienced colleagues have figured out ways to deal with these moments, fledgling doctors may not know how to process and vocalize their experiences, and there’s a risk that they’ll get overwhelmed by emotions or dissociate from them entirely. “Developing words to talk about the feelings makes them more understandable,” he said. “Communicating the feelings with colleagues who are going through similar experiences can not only make them more acceptable, but can hopefully keep the students away from the emotional isolation that is fertile ground for the occupational hazards inherent in our profession.”

There are no lectures in “Schindel-Time” and the format is unstructured: “The only ground rules are those I saw in my daughter’s preschool class—no hitting, no throwing, no spitting, no kicking,” Schindelheim said with a laugh. It usually takes a few meetings for the students to loosen up, but “you can feel the ease developing. I think of it as improvisational jazz. They’re all just doing their thing and riffing off each other.”

Beyond weathering pivotal interactions with patients, third-year medical students are also weighing career options against well-meaning feedback from advisors, parents, and residents that might conflict with their own inclinations. “Medicine is going to be hard enough, so go where the wind is behind you,” he said. “I always say that the best field to go into, is the field that you’re really into—where your passion points you.”

One way today’s students are different from when “Schindel-Time” started 36 years ago is in their reliance on technology, with email and social media beckoning from ever-present smartphones. “I tell them that they should not jump out of the room through their devices,” he said. “They should try to be with one another and be present.” Yet, much has stayed the same, Schindelheim said. “The emotional burden that all physicians have to wrestle with—coming to terms with that in some way has been a constant.”

This article originally appeared in Tufts Medicine Summer 2018.