-

About

- Departments & Offices

-

Academics

- Public Health

- Biomedical Sciences

- Physician Assistant

- Special Master’s (MBS)

-

Admissions & Financial Aid

- Tuition & Fees

-

Student Experience

-

- Student Resources by Program

- Academic & Student Support

- Wellness & Wellbeing

- Student Life

- Events & Traditions

-

-

Research

- Research Labs & Centers

- Tufts University-Tufts Medicine Research Enterprise

-

Local & Global Engagement

- Pathway & Enrichment Programs

- Global Health Programs

- Community Engagement

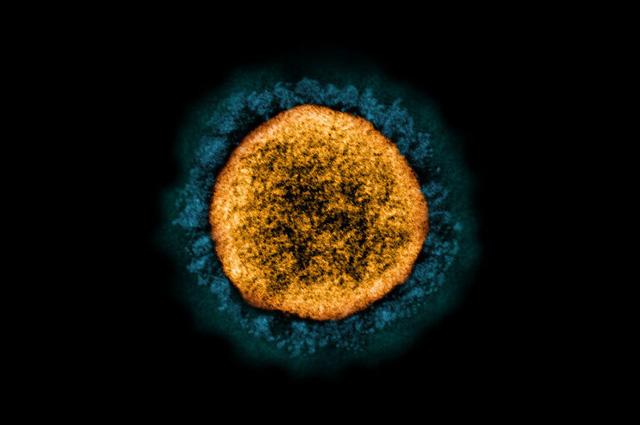

How Viruses Mutate and Create New Variants

As coronavirus variants circulate worldwide, a Tufts researcher explains the mechanisms of how viruses change and why it’s going to keep happening

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus pop up, and some lead to increasing infections. The main new variants—named Alpha, Beta, and Delta and first identified in Britain, South Africa, and India, respectively—have properties that make them more successful in transmitting and replicating than the original virus.

Viruses are not technically living things—they invade living cells and hijack their machinery to get energy and replicate, and find ways to infect other living organisms and start the process over again.

How viruses mutate largely has to do with how they make copies of themselves and their genetic material, says Marta Gaglia, an associate professor of molecular biology and microbiology at the School of Medicine. Viruses can have genomes based on DNA or RNA—unlike human genomes, which are made up of DNA, which then can create RNA.

Gaglia studies how viruses take control of infected cells and reprogram the cells’ machinery to reproduce themselves. “We’ve been working on a protein that the virus encodes that destroys the host RNA, blocking the cells from being able to express their own protein and blocking, among other things, antiviral response,” she says.

Tufts Now talked with Gaglia to learn more about how different viruses mutate and what it might mean for the COVID-19 virus and vaccines’ ability to stop its transmission.

Tufts Now: What is the difference between a DNA-based virus and an RNA-based virus?

Marta Gaglia: The main difference is that the genome can be a molecule of DNA or a molecule of RNA. Our genome and the genome of all cellular organisms is always DNA, but viruses can either encode their genome as DNA or RNA. Coronaviruses like SARS-CoV-2 are RNA-based viruses.

Can you briefly explain the difference between DNA and RNA?

They’re very similar molecules. DNA is almost always double stranded, and each of the sugars has a base attached: adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T). The A, C, G, and T pair up with each other; that makes it very stable as a molecule.

RNA is a similar molecule. Most often, it’s single-stranded. And one of the bases is different—it’s uridine versus thymine—but roughly speaking, it is the same thing.

Our cells normally have DNA genomes, which make copies of the DNA genomes when they divide.

Are there different varieties of virus genomes?

Viruses can have all sorts of different genomes: double-stranded, single-stranded DNA, single-stranded or double-stranded RNA genome—it just depends on the virus.

DNA and RNA have slightly different chemistry and the proteins that make them are slightly different. That has some implications for the mutation rates and for the kind of molecule that the viruses must encode to be able to survive.

If viruses have double-stranded DNA genomes, they kind of work the same way as DNA does normally in us, and they can use all the enzymes of the cell they have invaded.

But if they have an RNA genome like SARS, they need a special enzyme that will make a copy of the RNA, called RdRp.

And how do mutations happen? Are they different in DNA vs. RNA viruses?

There’s a complementarity between As and Ts, and Cs and Gs. Basically, you have one strand of either DNA or RNA and there’s an enzyme that facilitates the binding of the complementary base of As and Ts, and Cs and Gs. One base will pair and bind with the other base.

For instance, an A should pair with a T or U, depending if it’s DNA or RNA. But sometimes mutations occur if a wrong pairing happens. If A by mistake ends up pairing with, say, C, then that will be a mutation, because it will change the coding.

Our DNA-synthesizing machinery tends to have an error correction mechanism. It will figure out if there’s a problem, usually because the structure is kind of weird; if it’s not the right pairing, it will excise and repair the mistake. That happens during replication. It’s as if, while you were copying down a text and made typos, you could proofread and fix them.

The RNA-synthesizing machinery that most RNA viruses use to copy their genome doesn’t have this error correction mechanism. But coronaviruses have a special enzyme that allows them to do error correction, so they have a lower mutation rate than other RNA viruses. I don’t think it works quite as well as the DNA mechanism, though.

There’s this idea that because most RNA viruses cannot error correct, they make lots and lots of mistakes. That’s not great for us, because it allows them to mutate rapidly and avoid the immune system. But if they make too many mistakes, it’s not good for the virus either, because the viruses will just break down.

And when the replication does make a mistake and it’s not caught by the error correction, will the resulting virus be more successful or less successful?

There are three possibilities—mutations can do nothing, they can impair the virus, or they can facilitate the virus replication. If the virus transmits better, then it will more likely be selected [through evolution] to be dominant. If the virus transmits at the same rate, it’ll still transmit, but if it’s worse at transmitting, it’ll get lost.

We’ve seen in the pandemic that mutations have arisen and then they became really widespread and for almost all of the ones we hear about, it became clear that they have at least slightly better transmission. I don’t think it even has to be dramatically better. It just has to have a slight advantage over the original virus.

What else affects mutations?

The other aspect is that a virus will make hundreds to thousands of copies of itself every time it is in a cell. The chances of getting a mutant is high just because there’s so many replications happening.

Better transmission doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s more virulent, right? It’s just better at replicating and getting into the other cells?

Yes, it just means that the initial step of getting into cells is better. The development of the disease—the pathogenesis—has to do with many other things beside the replication of the virus.

Do variants of original viruses mix with other variants to create all new virus variants?

Each virus genome is alone, but you can imagine situations where you could have two viruses co-infecting the same cell, and in those cases, they might be able to compensate for each other.

There’s definitely evidence that some coronaviruses can recombine, too. It there are two genomes that infect the same cell—just like our genomes are combined during the division of the stem cells—they could recombine into a fully fixed genome as it comes out. Those events might be quite rare, but because the virus replicates in an exponential way, even a rare event has a certain probability of occurring.

Do vaccines for viruses need to be updated when variants arise? We get a new flu vaccine every year because it’s a different strain of the flu. Is that true with all viruses?

Some people are trying to develop a universal influenza vaccine, to try to target the antibody generation toward a part of the molecule that cannot change without making the molecule not work anymore.

With the coronavirus, we’re not that sophisticated. But I think the evidence is that the variants are not escaping the vaccine dramatically. Still, it’s something that people have definitely worried about and it’s possible that we might have to update vaccines.

And of course, that also depends how quickly we can get this vaccination round to complete—how many different variants are going to emerge by the time most people are vaccinated. But I don’t think there’s any evidence that it’s going to be quite like the flu.

How are influenza viruses different from coronaviruses?

They are RNA viruses, but they don’t have the “proofreading” ability that the coronavirus has, so they have a lot of mutations. They definitely seem to have adapted to really take advantage of rapid change; influenza seems to have developed a lifecycle that’s all about changing so much that you never build a complete resistance.

That’s not true for all viruses, though. The coronavirus definitely is not going to be like that. But if it does become endemic and it circulates in the population all the time, then there is a chance that a slightly different virus might emerge and we may need a booster.

Another question is, as people become immune thanks to vaccinations, is that going to be a strong pressure on the virus? Variants may emerge because people are immune to the old virus. Again, that’s much more likely with something like influenza that has a much higher mutation rate, than with the coronavirus.

Department:

Molecular Biology and Microbiology