-

About

- Departments & Offices

-

Academics

- Public Health

- Biomedical Sciences

- Physician Assistant

- Special Master’s (MBS)

-

Admissions & Financial Aid

- Tuition & Fees

-

Student Experience

-

- Student Resources by Program

- Academic & Student Support

- Wellness & Wellbeing

- Student Life

- Events & Traditions

-

-

Research

- Research Labs & Centers

- Tufts University-Tufts Medicine Research Enterprise

-

Local & Global Engagement

- Global Health Programs

- Community Engagement

Finding the Brain Pathway to Obesity

A new study reveals how leptin affects both weight gain and diabetes.

By Helene Ragovin

In 1994, great expectations greeted the discovery of leptin, the hormone produced by white fat cells that regulates weight maintenance and appetite. Would this be the key to ending obesity? Leptin normally signals satiety after humans and other animals have eaten enough to maintain body weight—or, stimulates appetite when calories are needed. But for almost a quarter-century, identifying leptin’s specific target in the brain has remained out-of-reach. “A dramatic amount of effort went into understanding leptin,” said Dong Kong, assistant professor of neuroscience at the School of Medicine. “Yet, sadly, from a neurobiological perspective, some very basic questions remained unsolved.”

Now, Kong and a team of Tufts researchers have unraveled some of the biggest mysteries about how leptin works in the brain, and opened the door to new clinical approaches for both obesity and diabetes, two of the world’s most-pressing health concerns. Their work identifying the neural pathway responsible for leptin’s role in controlling energy balance and appetite, and in regulating glucose in the bloodstream, appeared in the journal Nature in April.

The Tufts team’s findings have the potential to transform and accelerate all scientists’ work on leptin, with important implications for obesity and diabetes research. “This is very big translational progress. Now people have a target, a system that they can focus on,” Kong said

For Kong and his colleagues, finding leptin’s target in the brain became a matter of reframing the question. Most leptin studies used obese animal models. But, Kong observed, it was also known that obese animals suffer from leptin resistance—the hormone’s effects are blocked. “I was thinking, this kind of design is problematic,” Kong recalled. “Could there be some ideal mouse models, some ideal system for us to really evaluate the leptin effects and the real target?”

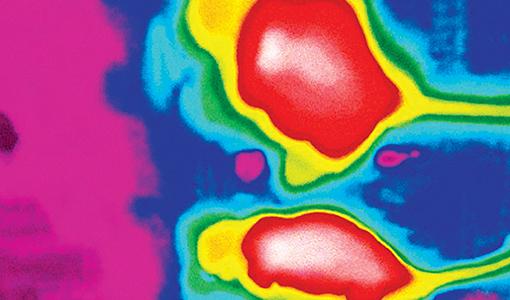

A hint came from research that showed injections of leptin could reverse Type 1 diabetes in mice having the condition. (Mice and humans with Type 1 diabetes produce extremely low levels of leptin.) To Kong, this was an indicator that Type 1 diabetes involves some sort of neural dysregulation in the brain connected to leptin’s activity. The researchers found that neurons in the hypothalamus—known as agouti-related protein-producing, or AgRP, neurons—were extremely active in the Type 1 mice, but quieted down after leptin was injected and the diabetes, in turn, was reversed. To further confirm that the AgRP neurons in the hypothalamus were reacting to the presence of leptin, Kong used CRISPR gene-editing technology to delete the leptin receptors in those neurons in healthy mice. The result: The mice became obese and resistant to insulin, turning diabetic.

The decades-old puzzle was solved—and with unexpected diabetes-related findings to boot. “This pushes our understanding of Type 1 diabetes to a different level,” Kong said. “People never imagined leptin could replace insulin and be used to treat diabetes.”

Translating these findings to human clinical trials, both for obesity and diabetes treatment, is still to come. The next big goal will be to understand more about what causes leptin resistance, Kong said, but he’s hopeful. “Based on our findings, it will be easy to come to other conclusions,” he said. “A lot of breakthroughs will be made very soon.”

This article originally ran in the Summer 2018 issue of Tufts Medicine.

Department:

Neuroscience